Key Facts: Cost-Sharing Charges

Updated August 2020

Health Insurance Marketplaces (also called exchanges) provide a way for people to buy affordable health coverage on their own. Health insurance plans available through the marketplace have to meet standards for the charges that people enrolled in the plan pay when they use medical care, which are known as cost-sharing charges. The following Q&A describes the different kinds of cost-sharing charges that plans may impose and provides details on the standards that plans available to individuals and families through the marketplace must meet.

What is a cost-sharing charge?

A cost-sharing charge is the amount an individual has to pay for a medical item or service (e.g., hospital stay, physician visit, or prescription) covered by his health insurance plan. Plans typically have three different types of cost-sharing charges: a deductible, copayments and coinsurance, although not all plans feature each of these three types of cost sharing.

What is a deductible?

A deductible is the amount that a health insurance plan enrollee must pay before the plan starts to pay for most covered items and services. The deductible is set on a yearly basis. For example, if a plan has a $1,000 deductible, an enrollee will generally have to pay the full charge (or total cost) for most medical services until she has spent $1,000. Once the deductible has been met, if the enrollee receives additional medical care during the same year, she would not have to pay the full charge for those additional items and services. The health insurance plan would pay a portion, and the enrollee would pay a portion based on the copayments and coinsurance that apply to the service.

Are all covered benefits subject to a deductible?

No. Under the health reform law, health insurance plans sold in the marketplaces have to pay the full charge for certain preventive care services delivered through the physicians’ offices, hospitals, pharmacies and other health care providers that are part of the plan’s network (in-network and out-of-network benefits are discussed below). Even if a plan has a deductible, the enrollee would be able to get these preventive services without having to pay a share of the cost.

In addition, some health insurance plans may decide to exempt other items or services, such as prescription drugs or a certain number of physician visits, from the deductible. In the case of prescription drugs, for example, the plan may pick up a portion of the cost of the drugs (rather than requiring an enrollee to pay the full charge) even if the enrollee has not yet met their deductible for that year.

What is a copayment?

A copayment is a fixed dollar amount that enrollees must pay toward the cost of a medical item or service that they use and that the health insurance plan covers. Copayments are common for prescription drugs and seeing a physician. An example of a copayment is when the enrollee pays $10 for a prescription drug and the plan pays the rest of the cost.

What is coinsurance?

Coinsurance is a fixed percentage of the allowed amount for a covered item or service that an enrollee must contribute (see below for a definition of what is an allowed amount). For example, a plan may require a plan enrollee to pay 30 percent of the allowed amount for lab tests. The plan would pay the remaining 70 percent of the charge.

For an explanation of common health insurance terms and an example of how cost-sharing charges work, see the Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) glossary.

What is the difference between in-network and out-of-network benefits?

Health insurance plans usually have a network of health care providers, with whom they negotiate prices for certain services. These doctors, hospitals, and other providers may be called “in network,” “preferred,” or “participating.” If a plan enrollee uses a provider that is in the plan network, the plan will pay some or all of the costs of the care delivered by the provider depending on whether the enrollee has met his deductible and the type of service.

Health insurance plans may also provide some coverage for services received “out of network” but may require enrollees to pay a higher share of the costs for these services. For example, a higher deductible, copayments and/or coinsurance may apply to out-of-network care than for care provided by the plan’s network of providers. In addition, the full charge (or total cost) of the service may be higher, because the out-of-network provider can charge more than the amount the plan has negotiated with providers in the network. For example, if an enrollee sees a physician who is outside of her insurance plan’s network, and the physician charges $150 for the visit, but the plan’s allowed amount (discussed below) is $125, then the insurer will pay only $125 minus any cost-sharing charges that apply. In addition to the cost-sharing charges, the enrollee would be responsible for the $25 difference between the allowed amount and the full amount charged for the service.

What is the “allowed amount” for a medical service?

As noted above, insurers usually negotiate how much they will pay for the costs of covered health care services with physicians, hospitals, and other health care providers in the health insurance plan’s network of health care providers. These negotiated amounts are known as the “allowed amount,” and sometimes the “eligible expense,” or “negotiated rate.” Health care providers participating in a plan’s network agree to accept these payment amounts when a person covered by the plan uses their services. The cost-sharing charges the enrollee owes (for example, a 20% coinsurance rate) are based on this allowed amount. If an enrollee uses a provider that is not in the plan’s network, the overall charge could be higher than the allowed amount. And the enrollee may be required to pay the excess, a practice known as “balance billing.” A provider participating in the enrollee’s plan network cannot balance bill the enrollee.

Is there any limit on the total amount of cost-sharing charges that an enrollee in a marketplace health insurance plan has to pay?

Yes, there is a “maximum annual limitation on cost sharing,” or a maximum out-of-pocket limit, that applies to all marketplace health insurance plans. This is the maximum amount that an enrollee is required to pay for all cost-sharing charges (including the deductible, copayments and/or coinsurance) during the course of a year. The health law requires each plan to have a maximum out-of-pocket amount that applies to covered essential health benefits delivered by in-network providers. Insurers may set out-of-pocket limits that are lower than these maximum amounts, and out-of-pocket limits for a family plan are limited to twice as high as the maximum amount for an individual plan. For 2021, the maximum out-of-pocket limits are $8,550 for individual coverage and $17,100 for family coverage. In a family plan, each individual enrollee must be protected by the maximum individual annual out-of-pocket cap, even if the overall limit for the family is higher. For example:

- William, Paula and their son, Sammy, are enrolled in a family plan with an out-of-pocket limit of $12,000. William incurs $10,000 in cost-sharing charges due to a hospitalization in May. However, because William is protected by the individual maximum out-of-pocket limit, he will only pay the maximum allowed out-of-pocket amount for an individual ($8,550 is the limit in 2021), and for the remainder of the year, he will pay no cost sharing. If Paula and Sammy have additional medical expenses and spend $4,100 on cost-sharing charges during the year, the family will reach their health plan’s $12,000 out-of-pocket limit and will pay no cost sharing for the rest of the year.

Will the maximum out-of-pocket limit change from year to year?

The amount of the maximum out-of-pocket limit for a health insurance plan covering an individual will be adjusted to account for changes in the cost of private health insurance. HHS announces the maximum amount for each new enrollment year in an annual notice. For 2021, HHS has announced that the maximum out-of-pocket limits are $8,550 for individual coverage and $17,100 for family coverage. The amount of the maximum out-of-pocket limit for a family plan will always be double the amount set for an individual plan, though the individual limit of $8,550 also applies to each person enrolled in the family plan.

What happens if an enrollee gets care from providers that are not in the health insurance plan’s network?

If an enrollee receives a significant amount of health care from providers outside of a health insurance plan’s network, she could pay more in total deductibles, coinsurance and copayments than the out-of-pocket limit, because the limit does not apply to cost-sharing charges related to out-of-network health care services.

What if someone gets a health care service that the marketplace health insurance plan doesn’t cover?

If an enrollee uses medical services that the health insurance plan does not cover at all, she would have to pay all of the costs out of pocket, and those costs would not be subject to the health law’s out-of-pocket maximum. This would be the case even if she got the care from an in-network provider.

Are people enrolled in a marketplace plan required to spend the full amount of the out-of-pocket limit each year?

No. Only a very small portion of people will have such large medical expenses that their cost-sharing charges will reach the out-of-pocket limit. But, the out-of-pocket limit provides critical financial protection for people with serious illness or injury and particularly for unexpected or catastrophic health care needs.

For example, if a marketplace health insurance plan enrollee gets sick just once in a year and goes to the doctor once and fills one prescription, she might spend $50 out of pocket in that year, depending on the charges for her care and the details of her coverage. But in the case of a very expensive illness requiring hospitalization, total deductibles, copayments and coinsurance could reach into the tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars if there was not a limit.

Who pays for health care services after a person’s total out-of-pocket costs reach the out-of-pocket limit?

After an enrollee spends the amount of the plan’s out-of-pocket limit in deductibles, copayments and coinsurance for in-network, covered benefits, the plan pays the full costs of any covered health care services that the individual receives from in-network providers.

Besides the out-of-pocket maximum, are there other standards related to cost-sharing charges that marketplace health insurance plans have to meet?

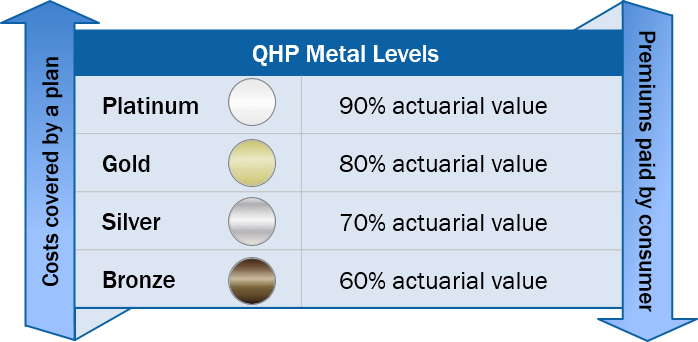

Yes. Most marketplace health insurance plans must be organized into coverage levels or tiers named for precious metals: bronze, silver, gold, and platinum. Plans are sorted into levels based on their actuarial value, which is a way to estimate and compare the overall generosity of different plans. (Actuarial value is explained below.) The more precious the metal, the higher the actuarial value of the plan, and the lower the cost-sharing charges, such as deductibles and copayments, that enrollees have to pay. For example, a gold plan generally has substantially lower cost-sharing charges than a bronze plan, which means that the insurance plan pays a larger share of costs when someone uses medical services (see Figure 1).

| FIGURE 1: QHPs Must Provide Plan Designs Consistent with Actuarial Value |

|

Are health insurance plans other than those offered through the marketplace — such as a plan offered by a large employer — subject to any cost-sharing requirements under the Affordable Care Act?

Yes. The out-of-pocket maximum applies generally to employer plans as well as plans in the individual market both inside and outside of the insurance marketplace. (Grandfathered plans — those that existed prior to passage of health care law and have not changed significantly since — are exempt.)

As for the requirements for exchange plans to be in metal tiers, they only apply in the individual and small-group markets and do not apply to plans offered by large employers.

Do all health insurance plans in the marketplace have to be in one of the metal tiers?

Marketplace health insurance plans either have to fit within one of the “metal” tiers or be a “catastrophic” plan. Catastrophic plans were created as an option for younger people. The plans have a very high deductible (equal to the out-of-pocket maximum, so $8,550 for an individual in 2021). This means that, with the exception of preventive services that have to be provided without any cost-sharing charges and at least three primary care physician visits per year (with enrollee cost-sharing allowed for all care that’s non-preventive), enrollees would generally pay the full cost of any medical care they might need until they spend $8,550. The catastrophic plans also are not eligible for purchase with premium tax credits.

Catastrophic health insurance plans may be attractive to people who want to pay as low a premium as possible, do not expect to need much health care, and are not eligible for premium tax credits. People younger than 30 are eligible to enroll in a catastrophic plan. People 30 and older are eligible to enroll in a catastrophic plans if they qualify for a marketplace coverage exemption because they lack access to affordable coverage or have experienced a hardship.

What is the purpose of the metal levels?

Organizing health insurance plans into levels based on the level of coverage they provide can help enrollees compare different plan options and decide which one is best for them. The metal levels also ensure that a basic level of coverage will be available. Federal standards require insurers participating in the marketplace or exchange to offer plans in at least the silver and gold levels.

What is actuarial value?

In general, the actuarial value percentages that apply to the metal levels represent how much of a typical population’s medical spending the health insurance plans in that metal level would cover.

Percentages (60 percent for bronze, 70 percent for silver, 80 for gold, and 90 for platinum) represent the actuarial value of plans at each level. A higher percentage means the plan covers more of a typical population’s costs (and the population pays less out-of-pocket). A lower percentage means the plan covers less (and the population pays more). The actuarial value calculation focuses mainly on cost-sharing charges, so that a bronze plan generally would have higher enrollee cost-sharing amounts compared to a gold plan. There also may be differences in how benefits are covered, such as differences in the prescription drugs that are covered or how many physical therapy visits the plan covers. The law requires all the metal level plans to cover a set of essential health benefits.

How is actuarial value calculated?

Actuarial value calculations are based on spending on health care services associated with a “typical population.” A “typical population” is a large group of people with a mix of health care needs. To determine the actuarial value of a health insurance plan, it is assumed that the entire typical population is enrolled in that plan. Data on the health care services used by the typical population are then used to figure out how much of the typical population’s costs the plan covers. This process takes into account the plan’s specific cost-sharing charges, including the deductible, copayments, and coinsurance. The actuarial value is an estimate of what the plan would spend on the benefits covered by the plan that are used by the typical population. So, a silver plan covers about 70 percent of the costs of a typical population’s costs for covered benefits.

Does that mean that people enrolled in a health insurance plan with a 70 percent actuarial value level have 70 percent of the cost of their medical care covered? So an enrollee in that plan would pay 30 percent of the cost?

No. The actuarial value of a health insurance plan is determined using a large population, which includes people who use little or no health care services and others that have significant health spending. The value of a plan’s coverage to a particular enrollee depends primarily on the health care the enrollee uses.

As an example, consider two people, John and Jane, who are enrolled in the same silver plan, as shown in Figure 2. They have very different heath care needs during the year and therefore have different out-of-pocket costs under the plan.

| FIGURE 2: Two People, One Silver Plan |

||

| Silver Plan: 70% AV, $2,000 deductible, $5,000 OOP limit, $1,500 copay for hospital admission after deductible, $30 copay for physician visit after deductible | ||

| Example: John | ||

|

3 physician vists | $300 |

| Insurer’s share of cost | – $0 | |

| John’s share of cost | = $300 | |

| Example: Jane | ||

|

Hospitalized, 3 physician visits, and 20 physical therapy visits | $7,300 |

| Insurer’s share of cost | – $3,110 | |

| Jane’s share of cost | = $4,190 | |

| Deductible Hospital copay Office visits |

$2,000 $1,500 $690 |

|

What will the cost-sharing charges be in the various health insurance plan levels?

In most states, insurers can decide what cost- sharing amounts they will charge enrollees, as long as the health insurance plan applies the required maximum out-of-pocket limit and designs the cost-sharing charges so that the plan meets one of the actuarial values associated with a metal level. In some states, such as California and New York, however, the marketplace requires insurers to offer certain standard plan designs. Table 1 shows some examples of cost-sharing charges that would allow four sample plans to meet the various actuarial value metal levels.

| TABLE 1: Examples of Cost-Sharing Charges |

||||

| Bronze | Silver | Gold | Platinum | |

| Deductible | $6,650 | $5,500 | $900 | $0 |

| Inpatient care | 40% (after deductible) | 20% (after deductible) | 20% (after deductible) | $350 / day |

| Physician visit | $35 | $30 | $90 | $10 |

Are the cost-sharing charges in marketplace health insurance plans always going to simply involve a yearly deductible, a uniform copayment or coinsurance for services, and a maximum out-of-pocket limit?

No. While some health insurance plans may follow that simple structure, there is a significant amount of flexibility within the federal requirements for insurers to do things differently and in a more complex manner. For example, a plan might have two separate annual deductibles, one for prescription drugs and one for medical care. A plan may have cost-sharing charges that are quite low for some services (for example $10 co-payments for physician visits) but a different cost-sharing structure (such as 50 percent cost sharing) for other services. The same covered item or service may itself have different cost-sharing charges; for example, generic drugs may require a $10 copayment, preferred brand-name drugs a $25 copayment, and other high-cost drugs 50 percent coinsurance.

Can the provider network for health insurance plans offered by the same insurer vary from one metal tier to another?

Yes, except in states that are creating standard plan designs such as New York. As long as a health insurance plan meets the actuarial value target (60 percent, 70 percent, etc.) and limits in-network enrollee cost-sharing charges to no more than the federally established out-of-pocket maximum, insurers in most states can determine the specific cost-sharing charges for each item or service, as well as the specific amounts of the deductible and out-of-pocket limit. So two plans in the same metal level could have two different sets of cost-sharing charges for enrollees, even though the two plans have the same actuarial value. As an example, Table 2 shows how two sample plans that are both within the silver level can have different cost-sharing charges.

| TABLE 2: Comparing Cost-Sharing Charges |

||

| Silver Plan #1 | Silver Plan #2 | |

| Deductible (Individual) | $5,500 | $3,500 |

| Maximum OOP limit (Individual) | $6,500 | $7,350 |

| Inpatient hospital | 20% (after deductible) | $500 per day (after deductible) |

| Office visit | $30 | $40 |

How can someone find out what the cost-sharing charges in the marketplace health insurance plans are?

Healthcare.gov and the web sites for the marketplace in each state displays final information about what the health insurance plans look like. This allows people to browse plans offered in their area and compare specific details such as cost-sharing charges under various plans. In addition, marketplace web sites must make available a form called the Summary of Benefits and Coverage (SBC) for each plan.

The form provides information about plan benefits and cost-sharing charges in a standard way to allow for comparison of the plans offered in the marketplace. The SBC also must be provided by insurers or employers for other health insurance plans.